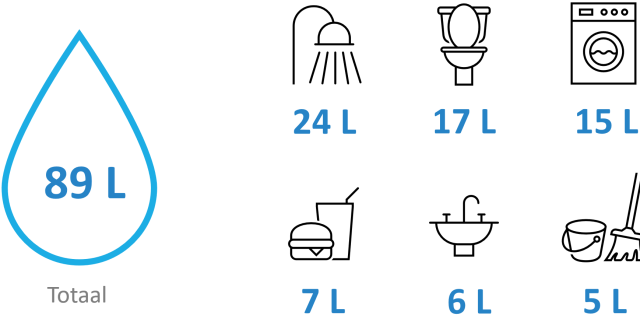

What if we only use drinking water for drinking? It seems trivial. Even though it is estimated that only 30% of total water consumption requires water of drinking water quality. Nevertheless, a few years ago the group of civil servants and designers involved in developing the Paterssite in Sint-Niklaas were unable to come up with an answer straightaway. The question emerged along with the idea of using the large roof of the chapel on the site to collect water for the rest of the site, which would include several dozen houses, built around the old square garden of a former monastery. “You’ll never be able to meet the water demand of all those homes with that?”, someone pointed out. Someone else asked what exactly the demand was. Around 120 litres per person per day was the design guideline, was the reply. And that is basically all drinking water from the water mains? Yes. But it’s not only for drinking water, apparently. After all, we also flush the toilet with drinking water. We water the plants or the lawn with it. We fill the swimming pool with it. We use it to wash the car. And ourselves. We cook vegetables in it, or make coffee with it. Pretty much without restriction. It is estimated that 1 litre out of 120 is actually drunk. If we include the water for preparing food, we end up with just 5 litres of the highest quality drinking water that we actually need. So, what if we just used drinking water for drinking? Instead of using the status quo, which will exert ever more pressure on our water supply, as the benchmark for new approaches, whereby unsustainable practices are set in stone for decades to come, take the preferred situation as a starting point for the design. We would explore that idea.

Where do you start? The idea prompted a lot of questions. The first wave of questions in this regard is how the various needs that drinking water from the tap currently meets can be met without drinking water. We introduced the idea of ‘reverse leapfrogging’. We generally assume that with our insights and technology we can help developing countries avoid the mistakes that we ourselves have made, so that those countries can ‘leapfrog’ straight to sustainability. The opposite concept, whereby we can learn a lot from them, is less familiar. And yet from a systems perspective there is a strong case for reverse leapfrogging, learning about solutions that need to work in a context of scarcity. Because, as we just illustrated, our systems were designed in a context of abundance. 120 litres of drinking water-quality tap water per day, per person, no questions asked, without flinching. Anyone who has ever visited India knows that you wouldn’t dare to reveal that fact over there.

That brought us onto a project in India in which we were involved. At the time, the project was just looking at the possibility of generating energy by fermenting the contents of dry toilets, for the kitchen of a local school where disadvantaged children received schooling. That’s right, dry toilets. In a context of scarcity, with no water, let alone drinkable water, people design dry toilets. European technology developers also design them. But you can hardly find them here in Europe, although we are starting to slowly see them appear, especially in the form of urinals. By a rough estimate, dry toilets could help achieve significant savings: about 20 litres per person per day, which is roughly one sixth of the consumption figure at the time. Take 50 houses with an average of 2 people (a conservative estimate). Then we save 100 x 20 = 2000 litres per day, so 14,000 litres per week or 728,000 litres per year. That simple calculation made an impression. Various figures are bandied about that deviate from this figure to some extent, but the aim was not to make an accurate calculation, but to see that playing around with assumptions is a powerful way to create new room for solutions.

The group was enthusiastic about seeing how far the idea could go. We discovered a second avenue to find alternative ways of meeting the needs: to get ideas, not only can you explore space, but also time. In the meantime, the idea of restricting the demand for water had become associated with the monastic life that had once taken place on the site. At that time, frugality was an important virtue. Not because of the limitation, but because of the freedom and comfort that came from that limitation, someone explained enthusiastically. They went on to highlight the importance of collectivity and connection with the surrounding community, which the monks had considered very important. Frugality as a comfort combined with the connection with the environment was updated under the idea of organising a laundry bar for the future residents of the site. In the neighbourhood next to the Paterssite, there was a laundromat that had been struggling for some time to attract customers. The idea emerged to invest via the project development in an ecological overhaul of the washing machines in the laundromat, in exchange for a laundry service for the residents. The new washing machines immediately reduced the impact of all the washing done by the other customers. The positive corollary effect of this idea emerged some time later. If the residents received a laundry service included in the purchase of their home, then a laundry room was no longer necessary, nor was the door to the laundry room, which also took up space. As a result, social housing could be built at a lower cost, without sacrificing living space. This drew our attention to a third, sometimes overlapping and sometimes complementary avenue for alternative solutions: multiple value creation.

Laws can prevent dreams from becoming reality, as can practical objections... The final project was unable to realise this vibrant creativity at this level of ambition, but the idea is still incorporated in the site’s master plan1. Nevertheless, in recent years, the idea has only become more relevant, and therefore merits much more thorough scrutiny. This brings us to a second set of questions: what is needed to realise these new solutions? You can find out by starting with the core idea, and then build the network around it, as it were, to make it work. For dry toilets, the toilets themselves of course, but also other ways of keeping them clean (no substances that affect the fermentation) and using the toilets, namely for men - in more abstract terms, different user practices. And if water is no longer used, does everything get adequately flushed into the sewers, or do these have to be modified as well? - in more abstract terms: different infrastructure. For our second example, the question is how the sketched revenue model can be translated into rules for the interactions between, and money flows between, all those involved, which take account of, for example, tax and mortgage lenders’ rules - in more abstract terms, different institutional or policy arrangements.

That brings us back to the laws and practical objections that stand in the way. If you know how to deal with them, they can become your allies. This is possible if you consciously use them to identify which new practices, infrastructure and arrangements are necessary.

We therefore invite Waterpreneurs to get started at the point of departure, at different levels of scale: at the level of a single home, at the level of an urban development or urban district, and possibly at the level of a stretch of riverbank covering the border between Belgium and the Netherlands, in order to investigate whether the reversal of the design logic might not even affect the water level in the Meuse. But the link with the energy transition is also relevant in this regard, because at a time when there are increasing calls for a major energy renovation wave of existing assets, the link to water infrastructure ought to be part of this.

In the spotlight: the project Water-conscious Building (Waterbewust Bouwen)

Within the VLAIO-COOCK project Water-conscious Building, we are looking for ways to make the built environment more resilient to drought and water scarcity by applying innovative technologies for:

- Rational water use;

- Circular water use with rainwater and gray water;

- and local replenishment of groundwater levels

Want to know more about the project? (in Dutch)

Download all catalysts

Disclaimer

The Flemish Environment Agency (VMM), De Vlaamse Waterweg, De Watergroep, Aquafin, the Flemish Department of Environment, Farys, Pidpa, water-link and VITO - Vlakwa have created the space for a group of fresh thinkers to develop a systemic view of water, and to challenge the water sector to shape a futureproof water system. The formulated ideas are not those of the initiators, nor do they represent their stands. However, they are considered valuable as an inspiration for the future of our water system.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.